I learned of the death of David Bowie today, and thought I’d post this piece I wrote back in 2007, my reflections about one of his greatest songs…

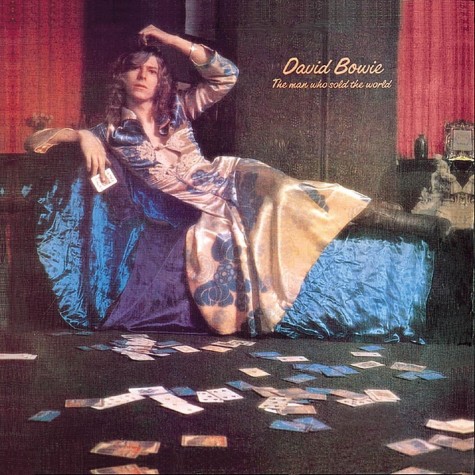

David Bowie’s “The Man Who Sold the World”

I’d never paid much attention to David Bowie. When he was becoming famous in the early 70’s, I had lost interest in rock and was delving into classical music, still playing my Doors and Janis and Beatles and Stones LPs, but ignoring the new crop. Thus, I missed Bowie’s classic albums, and by the time I started paying attention to rock again, we (and Bowie) had entered the era of disco, a sub-genre that I found both forgettable and regrettable.

Just recently, however, I started listening to Bowie, thanks to the recommendation of a friend, and in short order got the albums, The Man Who Sold the World, Aladdin Sane, and a two-disc Singles 1969-93 collection (Hunky Dory is on my must-buy list). On the first album mentioned, I came across the song that made me realize that for a third of a century I’d been missing the work of a musical genius.

The title song from The Man Who Sold the World has become my mantra, a song that I literally cannot get out of my head and have no wish to. Musically, lyrically, philosophically, it stands above 99% of Bowie’s other songs (at least the ones I’ve heard), 99.9% of the songs written during the time of its creation, and 99.99% of those written today. I need to write about it, if for no other reason than to examine why it’s made such an impression on me.

Musically, the hook gets in your brain and won’t let go. That A-A-A-G-A-B flat-A-G is a riff as simple as rainwater, but what’s most infectious about it is that it’s played over three different chords: D minor, A, and F. The melody of the riff is unchangeable. It seems to owe nothing to any key, and stands alone, adapting itself to the darkness of D minor, the brightness of F, and the intermediary and transitory character of A.

When the song shifts to a C chord (after “a long long time ago”), the thrice-repeated octave-long C-run and the following single F-scale create a churning, rising engine out of the chorus. Just when we think we’re on solid musical ground between C and F, Bowie drops in a B-flat minor chord (on “never lost”) which adds a textural complexity that suggests that maybe we are lost after all. But at the end of the chorus we slide down a half-step from B-flat minor to A major, a step toward home.

What’s most fascinating about “The Man Who Sold the World,” however, is not just the musical dexterity alone, but how Bowie relates the music to the evocative lyrics concerning duality, lost chances, and lives not lived. I’ll be up front and admit that I haven’t read any analyses of this song except for a rather brief one in Wikipedia, which makes the solid suggestion that the song might have been partly inspired by the poem:

Yesterday upon the stair

I met a man who wasn’t there.

He wasn’t there again today.

Oh, how I wish he’d go away.

Bowie takes this simple metaphor, however, and extends it radically. After passing upon the stairs, the narrator (the “self”) and the character he confronts (the “other”) speak “of was and when,” conveying in four words what other lyricists might have found required several lines. The story that follows might be seen as science-fictional, an epic tale of a man who literally sold the world and returns in some alien manner to tell an old friend. In that light, the lines “I thought you died alone/A long long time ago” to which the “other” answers, “Oh no, not me/I never lost control” suggests that the “other” might be the lost Major Tom of Bowie’s “Space Oddity,” and that “control” could be “Ground Control,” with which Major Tom never actually lost contact. (Though I haven’t read this interpretation, it’s so obvious that I assume I’m far from the first to suggest it.)

But what’s most interesting about the lyrics is not the surface SF story, but the psychological subtext and how it relates to its musical setting. The interpretation that I find most compelling is that of a man who meets his other self (or one of his myriad other selves) in a moment of self-awareness, realizes what he might have become, and considers the life he might have led if he had “lost control.” Through conformity, by never losing control of his emotions or his life, the narrator sells the world, gives up whatever other lives he might have lived in exchange for solidity and placidity, for a life which has neither excitement nor trauma. Still, that “other” beckons from time to time, and though the narrator thinks that aspect of his character “died alone, a long long time ago,” it still haunts and mocks him with the thought of what might have been.

When the narrator departs from the “other,” he tries to return to his home, searching “for form and land,” roaming for years and staring “at all the millions here,” the mob of undiscovered selves, duality multiplied to infinity. There is also a move from certainty to uncertainty: the first chorus states “Oh no, not me,” while the second changes the line to “Who knows? Not me.” The narrator has moved to unsure ground, not yet come home. And there is the suggestion that even if he does, home will never be the same again, now that he has been confronted with his new knowledge.

A more traditionally moralistic view is also possible (though less textually supported). It’s a mirror image of the above scenario, in which the narrator has sold the world – home, wife, family – in order to act upon his desires. He meets the “other,” the one who never lost control, but who recognizes in the narrator his other self, the man who did indeed sell the world. The rebuked narrator unsuccessfully attempts to go back home to reclaim the lost Eden, but finds “all the millions here” attempting to do the same.

Whichever approach one finds most appealing, there is no denying the underlying themes of duality and multiple personalities, and the suggestion that everyone has multitudes within them. The disquieting aspects of this are amplified by being placed upon a musical chordal structure that is just as disturbing as the underlying philosophical ideas.

The real brilliance of the song is the musical metaphor that Bowie uses, the constant, never-changing riff that fits harmonically with three individual chords, and whose character changes as it is played over each. It is a perfect illustration of how one personality, represented by one tune, can slip easily into very different lifestyles, represented by the changing chords.

While the original recording of the song fades out, in live performances Bowie ends the song on the unresolved A chord, leaving the narrator suspended, still uncertain, between the resolved “happy ending” of F major and the mysterious and unpredictable D minor. Thus the story remains unfinished and ambiguous.

There are songs that have equally compelling lyrical ideas, and songs that have as powerful melodic and chordal structures, but there are few that blend the two to create a work as cohesive, as compelling, and as haunting as “The Man Who Sold the World.”

This might be one of the best songs ever written. Thank you for your analysis. Bowie was tapped into something evolutionarily spectacular.

I came to this song through Kurt Cobain’s version on Unplugged, ages ago. I didn’t hear the original until fairly recently. I agree that the song won’t leave you alone once you have heard it, it tends to stay with you. Interestingly, there is a scene in Jason Bateman’s Ozark series about the difficulty in playing the chords just right. I’m so glad you wrote about this. Keep on Rockin.